Many legal scholars, digital‑rights campaigners and even some MPs now argue yes — the UK government has crossed the line between legitimate governance and systemic intrusion into private life.

The excuse used is often security or efficiency, but the effect is a government that increasingly trades people’s privacy for state convenience and corporate profit.

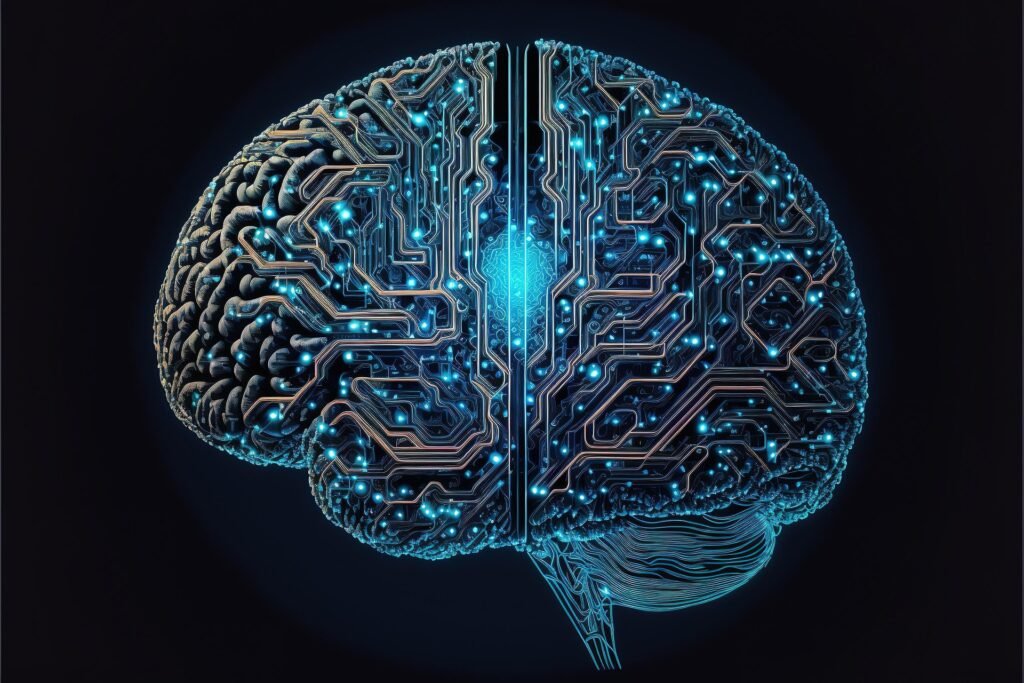

In the age of Artificial Intelligence (AI), data has replaced oil as Britain’s most valuable commodity — and the government appears much more concerned with exploiting that resource than protecting it.

Where Privacy Is Being Compromised

1. Expanding Surveillance Powers

The UK already operates under some of the broadest surveillance laws in the democratic world. The Investigatory Powers Act 2016, often dubbed the “Snooper’s Charter”, legally allows the government and intelligence agencies to collect citizens’ data in bulk — from phone calls and emails to online browsing history.

In 2025, Labour’s revised Data Access and Security Regulations extended automated data‑sharing agreements with tech firms under the banner of “national safety and fraud prevention.” In practice, these policies allow mass data pipelines feeding straight into government‑approved analytics systems, many managed by private AI contractors.

2. Partnerships with Big Tech

Major government functions — NHS digital services, policing analytics, benefits systems and migration data management — are now heavily supported by partnerships with global technology giants such as Palantir, AWS, and Microsoft.

Campaigners argue that these deals allow private companies access to enormous amounts of personal and health data under minimal scrutiny. The supposed anonymisation of sensitive information can often be reversed through cross‑referencing datasets, effectively exposing identities once again.

3. Weak Data Protection Oversight

Post‑Brexit, the UK has diverged slightly from the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) framework.

The government’s Data Protection and Digital Information Bill, still being disputed in Parliament as of 2026, aims to make data‑sharing easier for businesses and public bodies by “reducing bureaucratic barriers.”

Critics — including the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) — warn that the Bill weakens accountability, giving ministers power to define what counts as “legitimate” data processing without parliamentary consent.

Put bluntly: the watchdog is being told to sit quietly while the keeper rewrites the rules.

Advertisement

Why Does the Government Ignore the Risks?

1. Surveillance Is Politically Convenient

Governments value control. Mass data analysis allows them to predict, model and — cynically speaking — manage public sentiment.

From counter‑terrorism to welfare fraud prevention, data collection is sold to the public as protective. But the same data can be used to monitor dissent, manage public opinion or selectively target information to voters.

In an age of misinformation, the temptation to “nudge” behaviour via algorithms is too great for any ruling party to resist.

2. Big Tech Influence and Lobbying

Modern governments are dependent on technology firms to run critical systems.

A 2025 Transparency International UK investigation found that the top five digital‑infrastructure suppliers to government received over £7 billion in contracts between 2020 and 2025, often through non‑competitive tendering.

When the same companies fund AI training programmes, sit on government advisory panels and provide analytical tools to ministries, true independence evaporates.

Corporate power has quietly merged with public authority — a hybrid model where policy often aligns with private profit.

3. The “Public Apathy” Factor

Most Britons are aware of data tracking but rarely protest it. The trade‑off between convenience (digital banking, NHS apps, smart homes) and privacy feels abstract.

Governments and companies exploit that apathy: as long as the services work, people tolerate intrusion.

The cynical view is that privacy fails not because of what government takes — but because of what citizens are willing to give away.

What Can Be Done to Stop It?

1. Strengthen Independent Oversight

The Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) has investigative powers but lacks both budget and teeth. Expanding its independence, funding and authority could enable real enforcement — including penalties for government misuse, not just private‑sector breaches.

2. Increase Transparency on AI Contracts

Public sector contracts using AI analytics or data processing should be compulsory to disclose:

- The datasets involved.

- The algorithms used.

- The storage and deletion policies governing personal information.

If the government truly believes its data partnerships serve public good, it should tolerate full sunlight on their workings.

Advertisement

3. Digital Education for People

Most people surrender privacy because they don’t understand the value of the data collected from them.

Adding digital‑rights awareness to UK education — particularly people’s programmes — could create a generation less easily manipulated by convenience apps and persuasive government messaging.

4. Parliamentary Reform of Oversight Committees

Current privacy oversight committees, such as the Intelligence and Security Committee (ISC), review only a fraction of surveillance activities. Giving Parliament more access to classified auditing would prevent unchecked executive control.

5. Public Pressure and Journalism

Meaningful reform usually follows scandal. When investigative media (like The Guardian’s Pegasus Project or BBC Panorama exposés) highlight breaches, political action follows. Supporting independent journalism may be the single most effective defence of privacy in a data‑driven democracy.

Why Is It Not Properly Controlled?

1. Complexity Outpaces Legislation

Technology evolves faster than law. AI systems change weekly, while privacy legislation takes years to pass. By the time new rules exist, the original technology has already moved on, creating a permanent lag between innovation and accountability.

2. Political Dependence on Data Narratives

Data dashboards, forecasts and crime‑prediction tools make governance appear “evidence‑based.” Ministers prefer quick insights and real‑time analytics, even at the cost of transparency. It looks scientifically sound and allows convenient political messaging: “The algorithm says this works.”

3. Deliberate Ambiguity

Privacy law in Britain is dense and technocratic — hard for the public to challenge or even read. Ambiguity is useful: officials can claim compliance while operating in grey zones.

Cynically, the lack of clarity is the point — it keeps citizens uncertain, businesses flexible, and governments unaccountable.

The Real‑World Consequences

For People

- Gradual erosion of trust in institutions.

- Loss of control over personal data shared through government apps, digital IDs and AI analysis systems.

- Increased exposure to data leaks as private contractors store and monetise information.

For Business

- Larger tech firms gain a monopoly on government services.

- Smaller UK companies lose out, creating an anti‑competitive market controlled by multinational suppliers.

For Democracy

- Voter profiling and AI‑based campaigning distort elections.

- Data analysis replaces direct accountability; people become statistical subjects rather than active participants.

This isn’t dystopia from science fiction — it’s a quiet bureaucratic evolution already underway.

A Closing Thought

In theory, the UK is a democracy with data rights and legal oversight.

In practice, it is becoming a “data state” — one where the government’s desire for technological advantage overrides its responsibility to protect people from exploitation.

The uncomfortable truth?

Privacy rarely vanishes in one draconian swoop; it disappears transaction by transaction, consent by checkbox, partnership by memo of understanding between the public sector and Silicon Valley.

Only public vigilance, independent institutions and genuine transparency can slow the erosion.

If those forces remain weak, the UK’s promise of “digital empowerment” may simply become a cleverly branded system of perpetual observation.

References (UK‑Focused)

- gov.uk

- ico.org.uk

- Transparency International UK – Government Technology Procurement Report, 2025

- theguardian.com

- UK Parliament – Intelligence and Security Committee Annual Report, 2024–25

Summary

| Issue | Government Position | Reality | Proposed Remedy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection and security | Necessary for safety | Mass surveillance with private contractors | Independent oversight with real penalties |

| Big Tech partnerships | Efficiency and innovation | Privatisation of citizen data | Mandatory transparency and competition rules |

| Citizen rights under new laws | “Reduced red tape” | Weaker privacy protections | Avoid weakening GDPR standards |

| Oversight and accountability | Claimed as robust | Underfunded and opaque | Strengthen ICO and parliamentary scrutiny |

In conclusion:

Yes, the UK government is likely overstepping by prioritising data access over data protection — often in favour of political control and corporate gain.

It’s not properly controlled because neither the regulators nor the public have enough power or information to challenge it.

Reclaiming privacy will require new legislation, stronger institutions, and citizens who recognise that digital convenience should never come at the cost of personal freedom.